Getting diagnosed with cancer is a lot like falling in love. It starts slowly, and then it happens all at once.

A few months ago, I was sitting at my desk, mindlessly going through practice questions for an upcoming exam, when I felt it. While massaging my neck, there it was: a lump, no bigger than a pea, squishy to the touch. My medical student paranoia instantly kicked in, and the scenarios raced before me. It’s a lymph node. It’s lymphoma. I’m only 24 and in the middle of my surgery rotation, I can’t get cancer right now. After mashing the lump around for a few minutes, I took a deep breath and mentally slapped myself. How many times in the past couple of years had I diagnosed myself with a dangerous, life-altering disease? Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Pulmonary embolism. Breast cancer. The lump was small, mobile, slightly painful to the touch. All the textbook characteristics of a benign lymph node. I went back to reviewing my practice questions — it was a cyst, probably.

Fast forward a month, and one lump had become five. It felt like there were lima beans under my skin on the left side of my neck. I could feel them every time I swallowed. They hurt so much I developed my own pain regimen of two Tylenol every six hours. A visit to my primary care physician brought a throat swab, blood tests, and a nasal swab for COVID (just to be safe). Again, I was struck by another bout of medical students’ disease. It could be a bizarre case of strep throat. Or, it could be some fulminating bacterial infection just ready to burst forth from my neck like that scene in Alien. When my mono test came back positive the next day, I breathed a sigh of relief. Although I bemoaned the fact that I had gotten mono during medical school to all my friends, I was secretly glad that it was something so banal.

I was wrong.

For the next month, my lumps waxed and waned. They went from the size of pellets to nuggets to pellets again, a cyclic schedule of swelling and pain. I joked to my friends that it might be time to write a case report about me for a medical journal, but deep down I clung to my diagnosis of mono like a life preserver. Any time the fear of serious illness threatened to overwhelm me, I recited I have mono in my head like dogma. When I showed up for a neck ultrasound that my primary care physician ordered in the name of being thorough, I felt both confident and foolish. Confident, because there was no way this was something serious (I was 24! I had a positive mono test!). Foolish, because once I got my benign test results, I would feel stupid for putting so much energy fussing over something that wasn’t worth fussing over.

A day later, my primary care physician called. It was a Thursday, and the weather outside was absolutely beautiful. From my vantage point in the hospital, I could see the East River, the Chrysler building, midtown New York sprawled out in front of me. I wanted to come to New York City, because it had always felt like the most expansive city in the world, a place without limits. It was in front of this view, this view that had always brought me so much joy whenever I passed it on my way to and back from the hospital ward where I worked, that my primary care physician first mentioned the word cancer.

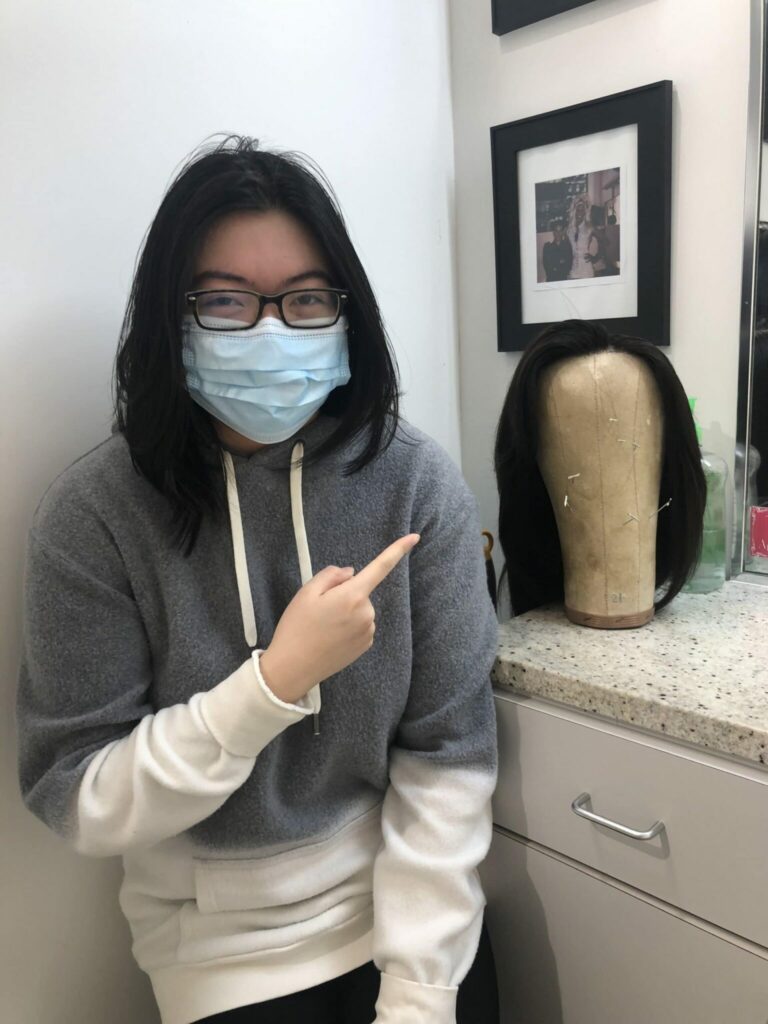

Over the next month, I was poked, prodded, scanned, and cut open. Every test that brought me further down the road of lymphoma brought with it a sense of crushing grief. I was 24! I had a positive mono test! I was a medical student, and I was having the time of my life! I did not want to have cancer. This was not the time to have cancer. Why couldn’t I get cancer when I was 80 and old and had already lived out my life? And, now the physicians were talking to me about my fertility. And how I was going to lose my hair. And how this cancer, the cancer I have, is curable — but it’s going to be hard, it’s going to be very, very hard for a while.

I would lay in bed, and think: Why me? Why did I have to get cancer? Why did I have to get cancer now? What if the treatment doesn’t work? What if the second-line treatment doesn’t work either? What if I’m one of those sad patient cases that’ll stick with my oncologist for the rest of her life? I want to live. I want to live so, so badly it’s a physical pain. I joked to my oncologist during our first appointment that I wanted to die with an MD after my name.

It’s not really a joke, though.

You see, I love what I do. I love taking care of patients, sitting down with patients, smoothing back their hair and holding their hand. I love explaining to patients and their family members what treatments we’ll be doing. I love coming up with plans to help patients and presenting them to the team on morning rounds. I love the thinking, and the doing, and the loving that comes with medicine. Even though I’m just at the beginning of my career, I carry so many names with me of people I’ve cared for. Mr. S, who taught me how to make his special weekend latkes. Ms. N, who I’d wheel down the hallways super-fast when no nurses were nearby. And on, and on, and on.

I don’t want this to stop. Please — I’ve just gotten started.

Getting diagnosed with cancer is a lot like falling in love. But love doesn’t have the potential of killing you. Love, in its best, most pure form, doesn’t threaten to take everything away.

The people around me have been telling me that I’m coping well. I laugh, I make bad cancer jokes, I just sat for a three hour exam and I think I passed (thoughts and prayers!). But, the truth is, there is no alternative to not coping because this is my life now. On December 23rd, I will be having a port put into my chest. On December 24th, I’ll start my first round of chemo. This, like medical school, is just the beginning of a long, hard road. And, there’s been plenty of times in private where I’ve cried and sobbed and thought about the Book of Job, and how I felt like Job, and I just wanted to not deal with anything and let the pestilence consume me. And, there’ll be plenty of times like that in the future too.

But, for now, I’ll still be in medical school. And, maybe I’ll have to take a leave of absence. And, maybe things will be delayed. But I will graduate. I will become a resident, and then a fellow, and then an attending.

This, I am absolutely sure of.

By Alice Zhao