When I was three years old, I was diagnosed with stage four alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. I remember sitting in that hospital bed — the second memory of my life. I remember the smell of the room. I later learned that’s how every hospital smells like, and now that smell makes me nauseous, but that was the first time I smelt it. Breathing in and out while in that hospital room felt like I was breathing an alcohol swab through a straw.

I had a lump in my hip. I didn’t know it. I didn’t feel it. I didn’t care. I was on top of the world, warm and comfy watching Thomas the Tank Engine on that dark silver box in the top left corner of the room. I was getting full room service, and cherry Jell-O was one call away. The doctors were talking with my parents outside the long gray room in which I lay, but I couldn’t care less what they had to say. Fourteen years later, I know what the hot topic was: I had cancer, and I was going to die.

The doctors said 20% was the magic number, and my parents clung tight to that 20%, 1 out of 5. 80% chance of dying before even living. 80% chance that I would never learn how to ride a bike. 80% chance that I would never go to school. 80% chance that I would never become a public speaker, a leader, an activist. I wouldn’t go on to become an actor or an NBA power forward. There was an 80% chance that I would go down as nothing other than a statistic.

The next memory I had was in an ambulance. I was on a comfortable rolling bed, because they wouldn’t let me walk, even though I had walked the day before. I heard sirens, and wondered who they were for. What emergency is there? I looked around, to see if I could find that person in need. The one whose struggles demanded the attention of everyone in that ambulance. There were plenty of nurses and paramedics and doctors, but they were all looking at me. I wanted to go back to watching Thomas.

In the hospital, I lived like a king. Every time something hurt, one of the best doctors in the world would be there to help me. Every time I was thirsty, somebody brought me water. My mother brought me powdered donuts after every scan, every surgery. And there were a lot of scans and surgeries. Even in the worst of times, I was still enjoying myself. The needles hurt, the beeping of the IV poles kept me up at night. But I was immortal. I couldn’t die. I’d meet a new friend every day, play with legos and train tracks, and not see them ever again, but they were immortal too. Death doesn’t exist when you’re three years old. If it does, I’m immune to it. I am superhuman.

I went through 7 surgeries, 75 days of maximum dose radiation to my head, hip, and pelvis, over a thousand days of chemotherapy, dozens of nights in the hospital, and a relapse at age 5. By age 7, I was done. The cancer was gone. I was starting to become normal again. I was working on my leg muscles, starting growth hormones, and making friends at school.

The Story Part Two: Here We Go Again

In May 2011, I was 9 years old. I wasn’t the cancer kid anymore. I was bald, and short, but I didn’t act like it. I had been done with cancer for three years, and wanted nothing more to do with it. No hospital, no cancer camp, no nothing. The night of May 24th I had a theatre performance, but the drama that night was nothing compared to the next day. I remember my parents telling me that my cancer was back. I was lying on my parent’s bed, face down on the white pillow that could barely absorb all the tears. I was dying inside, terrified of dying outside, and nobody would tell me I was wrong. They’d just look at each other helplessly, crying for me and crying for themselves too. I couldn’t even hold in everything I was feeling.

It was fine the first time, though the odds were just as bad. I didn’t know. You don’t tell a three year old that he’s gonna die, you just say that everything will be ok, and hope for the best. They all hoped for the best and it got me through. But this is the third time, and the prognosis is “no known cure.” I might be 9 years old, and I might be immature, but I’ve watched enough movies to know what death is, and I’ve certainly spent enough hours in hospitals to know what that’s like. They don’t have to tell me what’s about to happen. Between ages 7 and 9, I had become human again. I was in school full time, had lots of friends, and even trained to run a mile. I now knew that I would lose everything.

I remember being in treatment and going back to school when I felt well enough. Every time I tripped, it was an emergency. Kids carried my backpack because they assumed I was too weak. My friends treated me differently and I felt very much alone.

The Story Part Three: Something

One day in fourth grade, a paralympic skier named Chris Waddell came to speak at my school. When he injured his vertebrae and was paralyzed, he started sit-skiing, and he became one of the best sit-skiers ever. He told us, “It’s not what happens to you. It’s what you do with what happens to you.” This quote rang a bell in my head. It was the hope I was looking for. My mother had known about this speaker before he came to school, and she had made sure that I was in the front row. Now I realize why. It didn’t matter how everyone saw me. It didn’t matter that I was short or bald or anything. I had been through something that nobody else had been through, and now I was done trying to escape that reality. I wanted to use that experience for something.

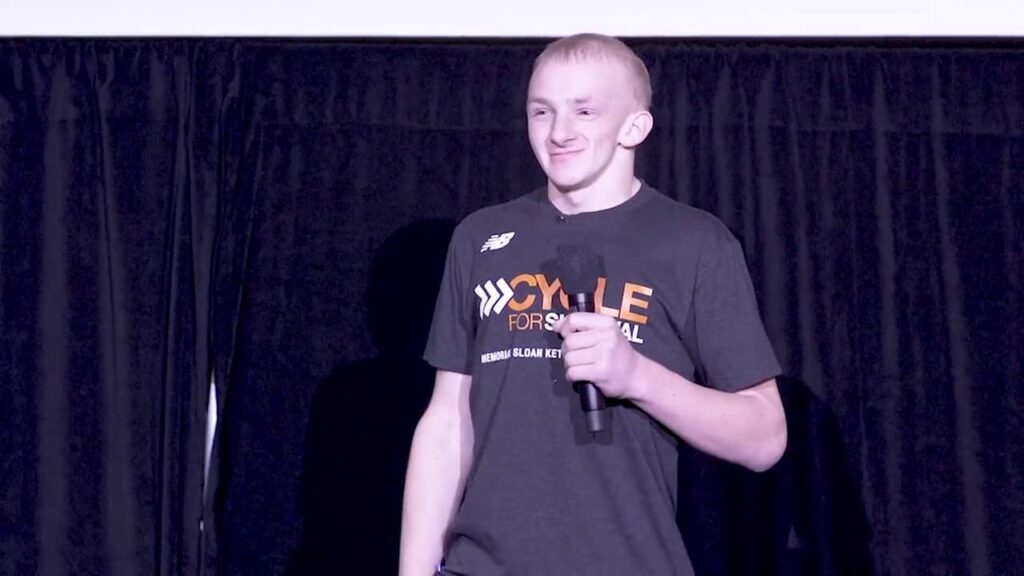

Months later, I was asked to speak at Cycle for Survival, a national movement to beat rare cancers. I was at this event, in Miami, with hundreds of people who were there for people like me. I’m not going to tell you that I was “overwhelmed with a sense of purpose.” I wasn’t. I was preparing to talk in front of a lot of people. They called my name, I got up there with nothing prepared and said a few things that came to me.

“What can I do? What can we do? We can’t just wish cancer away. What we can do is help Sloan Kettering find better cures and better treatments so that one day Sloan Kettering will be able to treat kids so that they don’t have to go through what I went through.” My story seemed to resonate with people. People who were going through cancer. People who knew someone going through cancer. Parents of the kids I had played with back when I was three. I could create real change.

I fell in love with sharing my story. Every year I give multiple speeches in New York, Miami, or Los Angeles, and I love seeing the lives I can impact. But I also see the work I can do. There are people who need my help. I am not a cancer fighter, but it is my responsibility to be an activist for progress in cancer research. I am no longer a victim. I am no longer a statistic. I am a leader.

The Story Part Four: Tate

My project of public speaking became ever more important in January of 2018. I was at my cancer hospital for an orthopedic surgery. It’s always an odd feeling going back to that place where I had spent half of my childhood, especially for such simple things. Here are the greatest cancer doctors and surgeons in the world, and they’re here for a simple hardware surgery for a kid who doesn’t even have cancer anymore.

It was a funny yet calming feeling, knowing that because I had spent longer at this hospital than most kids had (most likely because they either were cured sooner or otherwise), I was privileged with the attention of the doctors. After the surgery, I was placed into an inpatient hospital room, one I vividly remembered from back when I was nine or ten. In every room there are two patients, with a curtain to separate them. Rarely is this curtain removed. Removing it would force each suffering child to share attention with another, and while this will sound egotistical, that’s not fair. Every child in that hospital needs ten times the amount of love a normal child gets, just to keep them going. I was blessed with the health to give all of my love and all my family’s love to my roommate.

I met my roommate when I got out of surgery and I realized that he was me. A skinny eight-year-old boy with a few strands of hair at the top of his head, needles in each arm, an iPad that was out of battery, and a big smile on his face. His mom tried to make him talk to us, but he’s got an independence to him that doesn’t quit. He says with a southern accent, “I’m Tate. What’s your name?” I want to be Tate right now. I can already tell he’s going through intense treatment, but that smile is radiating throughout the room, vibrating my bones. He doesn’t give a care in the world, and he might be the happiest kid in the world right now. Even when I left the hospital, he kept a positive attitude. When I kept coming back to spend time with him, he kept a positive attitude, not paying attention to the fact that his condition was getting worse, not knowing that his treatment wasn’t working. We replayed the first level in the story mode of Halo: Reach on an XBOX 360 he rented from the hospital. He kept attacking his teammates, laughing with me, making small jokes, and those jokes were priceless.

My experience has changed the way I think about life and the world around me. For one, I am incredibly grateful for each second I have. In some ways, this has made me more pretentious— I almost died, three times, and so when I see people focusing on gossip and substances I feel that they are wasting their time. Cancer has made me optimistic and resilient. If I can go through eight years with my life on the line and come out as a leader and as an activist, then I can do anything.

I used to isolate myself, feeling that because I had gone through things that nobody had gone through, I wasn’t on the same level as other people. Who was on the higher level was something I was unsure of. But everyone has experienced pain. Some people have less pain, some people bring their pain upon themselves, but everyone’s got something. I used to repeat this line that my great-grandmother used to say: “If we all threw our problems in one bowl, we would look around and rush to take our problems back.” I don’t agree with this statement because there are definitely some problems I’d prefer to have over mine. But you get the point. People are going through things that you couldn’t even imagine, and you are probably going through something that would scare most people. That’s just life, and it’s not fair.

Tate passed away in September of 2018, and all of these things that I had been telling people in my speeches about making sure no kid goes through what I went through became real. Tate went through the same suffering I did, but he wasn’t as lucky as I am. To me, this tells me that I am nowhere near done with speaking, and contributing. I may not be a poster child anymore, but I feel that it is my responsibility to make sure that the Tates of the future survive to have long, happy lives. My battle with cancer is not over, and so my story is not complete. I can’t wait to see where it goes.

By Luke Weber

This story is made possible by: